BOOK DETAILS

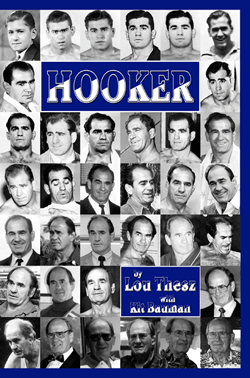

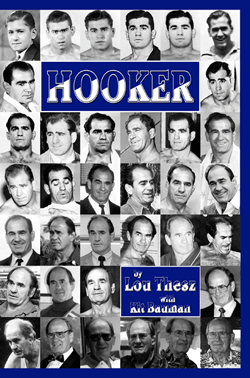

Paperback: 285 pages

Dimensions: 6x9

Publisher: Crowbar Press

Photos: 215 b&w

Cover: Full color

ISBN: 978-0-9844090-4-4

Item #: cbp13-lt

Price: $19.99

|

PRIORITY MAIL UPGRADE

|

ORDER BY MAIL

CLICK HERE

|

CREDIT CARDS

CLICK HERE

|

INTERNATIONAL ORDERS

For orders of

more than 3 books

please contact us at

|

|

|

"HOOKER" is available exclusively from Crowbar Press.

All books will be shipped via Media Mail (U.S.), Priority Mail, or International Priority Mail (Canada/overseas).

Who was the greatest pro wrestler of the 20th century?

The debate is a real one among those who seriously study the history of this American pop-culture creation. Like the arguments over any effort to crown "the greatest," "the best," or "the worst," that answer is unlikely to ever be resolved to everyone's satisfaction. One fact is indisputable, though. For those who watched wrestling before it became "sports entertainment," there is only one answer — Lou Thesz.

The son of European immigrants, Thesz discovered his love of amateur wrestling as a shy eight-year-old, scuffling with his father at night on the linoleum floor of the family's kitchen in south St. Louis. He was a natural at the sport, blessed with lightning-fast reflexes and a determination to succeed. He was obsessive about conditioning and hungry to learn, and those qualities eventually led him, as a teenager, into the closed and secretive world of pro wrestling, the only place where he could continue to compete on the mat.

This is Thesz' story — an adventure that took him to the heights of his chosen profession at a very young age and eventually into rings throughout the world. A devoted fan of pro wrestling, he won the respect and friendship of many of the legends. In the 1940s, when television demanded more action and a flashier style of wrestling, he became the transitional figure, the link to the past. Thesz decried the rise of "gimmick" performers like Gorgeous George and Buddy Rogers, who diminished the importance of the authentic style of wrestling he loved and practiced, but he adjusted because the bottom line of pro wrestling, as with any pro endeavor, was making money, and he could see where the future lay.

In the late 1940s and well into the 1950s, he was the world heavyweight champion of the National Wrestling Alliance, its standard-bearer, and he carried those colors with dignity and class. "My gimmick was wrestling," he said, and it was evident to anyone who ever bought a ticket to see Lou Thesz that he was the real thing.

"Hooker" was something of a sensation among wrestling fans when it was first published in the 1990s because it was among the first accounts ever published by a major wrestling star that discussed the business with candor from the inside. Academics praised the book, too, for its clear depiction of an era and the rise of a cultural phenomenon.

This is a book for everyone with an interest in professional wrestling. It contains pages and pages of new material — stories, anecdotes, and 215 classic photos — none of which has been published in any previous edition and all in the voice of one of the legendary figures of the game. Every sentence has been thoroughly combed over and vetted in order to answer any questions previously asked by readers, or to correct and/or re-order the "facts" as Lou recalled them, and each chapter now has detailed endnotes to further supplement the text. Combine all those ingredients with all-new, spellbinding forewords by Charlie Thesz and Kit Bauman (comprising 26 pages), an extensive 32-page "addendum" in Lou's own words, and a comprehensive name-and-subject index, and you have the definitive tome devoted to wrestling's golden era.

This is "no holds barred" material — far more open and truthful than anything ever written about professional wrestling.

Excerpt from Chapter 2

Copyright © Charlie Thesz & Kit Bauman

Another occasion I remember vividly involved George Tragos and a referee named Fred Voepel who had a bad habit of snatching the wrestlers during their matches. It was a very dangerous action for the boys because it could cause them to screw up their timing and cause someone to get hurt. When the fool grabbed George one night during a match, George told him in no uncertain terms to never do it again. One word led to another and George ended it by inviting the ref down to the gym to settle the issue on the mat. Imagine our amazement when Voepel actually showed up. A bunch of us were watching from the bleachers as they went at it, and we knew it was only a matter of time before Tragos hooked the guy and hurt him.

Sure enough, Tragos nailed the guy to the rack within a couple of minutes with what's known as a top scissor with a cross-face, an excruciating hold for the guy who's on the bottom, and we could hear clearly as one by one, like dominoes falling, Tragos dislocated Voepel's vertebrae. That's the kind of damage a hooker could do to an opponent. The ref was carried off the mat, partially paralyzed, and he spent about three weeks in the hospital recovering. Tragos just shrugged it off.

Excerpt from Chapter 3

Copyright © Charlie Thesz & Kit Bauman

Another interesting character from those days was a tough old carnival wrestler named Earl Wampler. He had semi-retired from the business by the time I met him and was a wealthy corn and hog farmer, but he loved the wrestling lifestyle and would occasionally accept a booking just for old-time's sake. I wrestled him on a card at a softball park in Waterloo and made $50, the biggest payoff of my young career, enough to pay my hotel bill for a month, so I would have remembered him fondly even if I'd never seen the man again. As it was, he took a liking to me and became an occasional workout partner.

More importantly, Earl Wampler opened my eyes to the easy availability of women. During my night-time outings with Ray Steele back in St. Louis, I had seen firsthand just how attracted women were to pro wrestlers — they were the macho jocks of the era, long before Americans even acknowledged the sexual allure of famous athletes — but Wampler was the one who really eased me into the marketplace. He was living part of the time with a widow in Osceola, a small town south of Des Moines. One time, he decided to drag me along and introduce me to the woman's daughter. One thing led to another and I ended up being a regular visitor. Earl would stay in one bedroom with the mother while the daughter and I occupied another. Thanks to him, and the girl, of course, just the mention of Iowa still puts a smile on my face.

Excerpt from Chapter 5

Copyright © Charlie Thesz & Kit Bauman

But not too long afterward, something happened that almost sent me back to my father's shoe-repair shop. I was working out regularly with the big boys in St. Louis by then and I was becoming rather cocky. Everyone kept telling me how much I was improving, pumping up my confidence, and I suppose I figured that I was close to being a world-beater.

One day, Ed Lewis came to town, en route to a booking somewhere as a special referee, and he dropped by the gym. A lot of the boys began telling him about this young hotshot he ought to work out with, and Ed, who was always curious about new talent — and who feared no one when it came to a contest — was more than willing to do it.

I must have been crazy because I actually thought I could take him. I was in tremendous shape and had been holding my own in workouts with some of the top wrestlers in the St. Louis office, so I was anxious to show my stuff. One thing I definitely had going for me was speed. I was a legitimate heavyweight by then, about 220 pounds, but I had the God-given reactions of a quick middleweight, which awed everyone around the gym. "Go for the single-leg takedown as soon as you get in there and take him down," they told me as I prepared for the workout with Ed. "You're way too fast for him, Lou. There's no way he can stop you."

When we came out onto the mat, Ed looked at me and said, "Hey, I remember this kid. We met last year in Des Moines." He couldn't have been more cordial, and I was flattered that he remembered me. He was genuinely trying to put me at ease.

"Now, look, kid," he said, just before we started. "Forget who I am, okay? As far as you're concerned, I'm not Ed Lewis. I'm just another wrestler. This is a friendly workout and I've got nothing to prove here, I'm just interested in seeing what you've got, so give it your best." And then we went at it.

It was an educational experience, in terms of both wrestling and humility. Ed Lewis was 46 years old and out of condition, but you couldn't tell it by what happened that day. My first move was the single-leg takedown. I faked for his head and then dropped to the mat, reaching to snatch his leg ... but it wasn't there. Before I could react, he was behind me, one of the points of advantage in both pro and amateur wrestling, and that's where he stayed. I couldn't get him off of me. I tried everything I knew, but he stayed right there. It was the longest 15 minutes of my life. Finally, he called an end to it. He helped me up, shook my hand, and slapped me on the shoulder. "Good workout, kid," he said. "You did okay."

Excerpt from Chapter 9

Copyright © Charlie Thesz & Kit Bauman

It's not a boast for me to say the Alliance liked having the belt around my waist for reasons other than my ability to draw money. I had a reputation by then as a serious hooker, and I had been around long enough to know I had to have my hands up every time I went in the ring. That appealed to the Alliance members because they could use me as a policeman to protect their promotions from outside challenges, and it actually happened a few times over the years. If an NWA promoter was having trouble in his territory with an outlaw promotion, he could settle matters by threatening to have me come in and humiliate the other promoter's top hand in a contest.

The Alliance members also liked having a wrestler as champion because they were naturally leery of each other. The so-called "brotherhood" of the Alliance was a facade, and everybody knew it. Some of them were truly fine people, and a few became valued friends of mine, but the majority was composed of thieves. The one quality all of them shared was a suspicion of each other. Whoever controlled the wrestler wearing the title had a step up on everyone else because he could demand preferential treatment when it came to using his boy, and use that as leverage to occasionally get a piece of someone else's action by demanding an additional booking fee for himself. It wasn't farfetched to believe that an NWA promoter might even decide to steal the belt and put it on his own boy. Having a champion who could actually defend himself against a double-cross was protection against that ever happening.

It wasn't enough to keep people from trying, by the way. I had a handful of title matches where I could sense something was amiss, or where my opponent had a special relationship with the referee, and I handled all of them in a direct fashion: I hooked the guy and threatened to hurt him if he didn't behave, and that was usually enough. If my opponent was an accomplished wrestler and I had reason to be suspicious of the ref, I'd handle matters by staying near the ropes — so I could duck under them or crawl out if I got in trouble — and never letting him get me into a compromising position.

Excerpt from Chapter 11

Copyright © Charlie Thesz & Kit Bauman

Johnny Doyle, who was instrumental in getting Gorgeous George started, was no saner than his partners. I remember one night when he stopped by the office building on Sunset that Mel Traxel and I owned. I used to keep maintenance costs down by doing a lot of the work myself when I was in town, and I had been refinishing the floors when Doyle passed by and spotted my car. He and his date were headed for a party and had stopped to invite me to come along, but I declined, saying I'd catch up with them later.

I walked with them back to his car and watched as they drove off. Just as I was turning around and heading back into the building, I saw another car down the street pull away from the curb and speed off after them. As it went by, I recognized the driver as another girl Doyle had been seeing, a seriously jealous type. I thought, "Hell, she's likely to shoot Johnny if she catches him," so I locked the building and jumped in my car to follow them.

It was just like a movie chase, these three cars speeding around curves and up and down Coldwater Canyon. It was obvious that Doyle had spotted the girl, too — she was driving a car he had given her — and he tried to outrun her, but she stayed right on his tail and rammed him whenever he slowed for a turn. It was funny in a way — she was beating the hell out of both of his cars.

Finally, on Ventura Boulevard, Doyle stopped at the curb in front of a large department store and ran inside with his date. The other girl drove her car right up on the sidewalk and tried to run them down. Instead, she smashed into the building, right through a huge plate glass window. Well, that ended the chase. The store people called the cops, the girl was arrested, and Doyle calmly got into his car and drove away. Maybe he was still headed for the party, I don't know. Later that night, when he figured she'd had time to cool off, he went down to the jail and bailed her out.

Excerpt from Chapter 12

Copyright © Charlie Thesz & Kit Bauman

All those thieves under one roof at the annual conventions was something to behold. One of the early meetings was a real fiasco, which said something about the membership. It was at the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas, the place that gangster Bugsy Siegel opened and ran before the mob eliminated him. Mike LeBell, who was the son of Aileen Eaton, Cal Eaton's wife, had booked it for the convention, and no one could understand why. The place was badly run down and the air conditioning was off, even though the convention took place during the dead of summer. It was a miserable experience for everyone, and we learned later that Mike LeBell's gambling habit was the reason we were there. He had run up a large tab at the casino, and getting the NWA convention booked there was his way of paying off.

At another NWA convention, also in Las Vegas, I asked the members for help in getting some films of wrestlers I had arranged to book in Japan. I needed to send the films over to publicize the wrestlers, but no one was inclined to help because several of them were negotiating for the same deal. All my years of effort for them obviously didn't mean anything, so I was pretty discouraged and disgusted when we broke for lunch.

Ray Gunkel, who had been a great amateur wrestler at Purdue and another one of the guys I always enjoyed working for, came to my rescue. He had become a successful promoter in Georgia and had a very good television show. He invited me to join him for lunch and, almost off-handedly, said I could have his films. As we were headed downstairs, we passed a group of NWA members who only minutes before had been swearing love and brotherhood to each other. One of them was saying as we walked by, "Don't worry, we'll take care of that sonofabitch," referring to another NWA promoter who had been part of the meeting. Ray and I had to shake our heads and laugh. Some of those people had ice water for blood.

Excerpt from Chapter 14

Copyright © Charlie Thesz & Kit Bauman

When I returned from Japan in October 1957, only a small handful of people — Ed Lewis, Sam Muchnick and the members of the National Wrestling Alliance's championship committee — had any idea that I was about to become the NWA's ex-heavyweight champion. I had notified Sam by letter from Australia that I'd had enough. "You can have your belt back," I told him, "just as soon as I fulfill my dates with Rikidozan."

Given what happened to me in Australia and Singapore, maybe it seems like a stupid decision to become a free-lancer. To be honest, that was what was running through my mind when I headed for Japan after the unpleasantries in Australia and Singapore. What I found there eased my concerns, though, and reassured me that I'd made the correct choice. Riki didn't care whether I had the NWA title or not. It was my reputation that counted with him and the fans, and he definitely wanted me back. Europe also looked very promising. Ed Lewis had been in touch with some influential people there who said they'd be happy to book me, so I was anxious to end matters with the NWA.

I admit I couldn't resist gloating a bit when I got back to the States and sat down with Sam to discuss what we were going to do with the title. Sam and the NWA had sold me to Riki for the Japan tour for $10,000, and I had protested when I learned about the deal. "That's crazy," I told them. "We could get $25,000 … $10,000 for me and $15,000 for the NWA." They were afraid to ask for that much money, though, so they went ahead and made the deal.

"You people are giving away the store," I told Sam when I returned. "Remember when I told you that $10,000 was too cheap a price for the booking? Well, even Rikidozan admitted as much. Let me show you what he's paying me to come back over there next year." I stuck a piece of paper under Sam's nose and grinned as I watched him read the bottom line: Riki was paying me $50,000 for two matches, and I wouldn't be splitting it with the NWA. Or anyone.

"That's the kind of money you guys are passing up," I said when Sam had finished looking over the contract. "The NWA has got a lock on this business, but you people are running it like small-timers. It's more important to your members to have the champion working tank towns for a $50 payoff and not even recovering his expenses, when he could be out there making this kind of money. That's why I'm giving you back your title."

I guess you could call it rubbing salt in an open wound. Relations between Sam and me had become so strained by then that neither of us was interested in trying to smooth things over. Sam wanted me out of his hair, as far as the NWA was concerned, and I was anxious to get to Europe. Things went smoothly during the three or four weeks I was in the States. I only wrestled a handful of dates, and no one called me at home, begging me to do them any favors.

Sam and the championship committee had huddled together while I was making my Far East tour. By the time I returned, they had decided whom they wanted as the new champion: Buddy Rogers. Given that Rogers was easily one of the top two or three attractions in the business, it was a sensible choice, and putting the belt on him would probably draw some very big houses.

I refused to do it, though. I hadn't changed my attitude about Rogers and wasn't about to give the belt to him. The NWA couldn't do anything about it, either. I told Sam that if he insisted on making the match, then I'd just go out there and beat Rogers straight-up, which wouldn't have been any chore. I had too much respect for myself and the wrestlers who'd worn the belt in the past to give it to a performer, especially one I'd never cared for personally. "If you want the belt back," I said to Sam, "get me a wrestler."

Excerpt from Chapter 15

Copyright © Charlie Thesz & Kit Bauman

Ironically, the one match I remember best from that three-year reign is one that never took place: a 1965 title-versus-title match between me and Bruno Sammartino. It would have united two of the three existing titles and made an awful lot of money for everyone involved if it had occurred, and I'm sorry it didn't. The only satisfaction I derive from thinking about it is that I once again — and for the final time, as it turned out — repaid Toots Mondt for the way he had treated me and all the boys almost 30 years earlier in southern California.

It was the New York swifties who suggested the match. They called Sam Muchnick and said they wanted a meeting to discuss some mutual business, so Sam and I flew to Chicago to meet them — Toots, Vince McMahon Sr., and my old friend Frank Tunney, the promoter in Toronto, who was loosely affiliated with the New York office by then. There, in a suite at the Morrison Hotel, they made their pitch: a title-versus-title match between Sammartino and me at Madison Square Garden, with closed-circuit TV into another New York arena and as many other cities throughout North America that they could line up. Closed-circuit TV was still a fairly new thing in those days, used almost exclusively to televise big heavyweight boxing cards, but the New York people had researched it enough to believe we could make a million dollars from that alone. The live gate at the Garden, with jacked-up ticket prices, was probably good for another $200,000, they said.

As for the match itself, they wanted me to lose. In return, they said, Sam and I would get $25,000 in cash, in advance, as a sign of their personal guaranty that Sammartino would meet me in a rematch within a year and drop the NWA title back to me. That was supposed to be our entire fee.

Sam was enthusiastic from the start, and he started to lobby me almost immediately in favor of making the match. I listened to all of this attentively, saying very little while I ran the numbers through my head. Finally, after a couple of hours, I agreed to do it — but only if they would meet my price.

First of all, I said I wanted $100,000 for myself, in advance — in other words, my usual 10-percent fee, from the supposedly "guaranteed" million-dollar gate from closed-circuit TV. I also wanted 10 percent of the Madison Square Garden gate, whatever it turned out to be, and I wanted it in cash the night of the match before I stepped into the ring. And finally, I said, I wanted three percent for Ed Lewis because he had done a fabulous job for the NWA and for wrestling in general over a long period of time, and he deserved to have a piece of a record-breaking gate like the one we had been discussing.

Well, Toots and McMahon looked at each other in shock. They had figured the $25,000 cash guarantee for the rematch would be enough to satisfy us, but I saw it as an insult, and I said so. I could earn that much with the NWA title in two weeks, so it was worth a lot more than what they were willing to put up. That was the centerpiece of my calculations. The NWA belt was so valuable I figured Toots and McMahon had no intention of giving us the rematch. They'd probably just forfeit the money and keep the belt.

McMahon finally spoke up. "We shouldn't be required to put up that kind of money in advance," he said. "We ought to enter into this pact with mutual trust."

That was almost enough to make me laugh. Trust them? I knew enough about both of those people that I would have been a fool to not insist on my money up front. "Those are my conditions," I said, "and I won't budge."

Toots stood up and said in a warm, sincere tone of voice, "Lou, I'd like to talk to you alone." The old fox could see that he had Sam convinced and that I was the only remaining hurdle.

We went into the bathroom, closed the door, and Toots started talking. "Look, Lou, we've had our differences over the years, and I know from my good friend Ed Lewis that you're not easily swayed once you make up your mind, but we're both reasonable adults. So, strictly between us, here's what I'll do if you go along with us: Immediately after the match, I'll personally give you a $25,000 bonus, out of my own pocket. And you can sleep on that."

I looked at him while he was talking, remembering those days in Los Angeles when he was paying us $10 a show and putting at least $5,000 in his pocket every week. I was remembering, too, all the stories about his petty thefts, cons, and hustles. I couldn't stand being in the same room with the man.

"Toots," I said, when he finally stopped talking, "you don't have enough money in your pocket to pay for the coffee you've been drinking this morning. You want to know what you can do with your $25,000 bonus? You can write it on a stiff check, and then I'll tell you where you can stick it. This is a business deal, and if you and that other thief can come up with $125,000 in advance, then we'll do it. If you can't, then we won't. Meanwhile, keep your charming bullshit to yourself."

I turned around and walked out of the bathroom, leaving him standing there. Well, Sam could see immediately that I was hot, so he asked the group to excuse us for a moment. I knew he was angry with me, too, and I couldn't really blame him because he stood to make some real money from the deal.

|

Foreword by Charlie Thesz

Foreword by Kit Bauman

1

Lou's overview of professional wrestling ... Barnstormers and carnies

2

Lou's introduction to wrestling ... Wrestling in St. Louis in 1924 ... Learning the Greco-Roman style of wrestling ... Wrestling at the St. Louis Coliseum ... The Business Men's Gym ... Wilbert Meyer beats up Lou ... Dropping out of school ... Meeting John Zastrow, referee in St. Louis ... Realizing there was more to wrestling than what met the eye ... Training with Joe Sanderson ... Lou's debut match in East St. Louis, Illinois ... Wrestling for promoter Rve. R.M. Gunn ... Buying his first car, a Model A Ford ... Meeting Tom Packs, the St. Louis promoter ... George Tragos, the first great influence on Lou ... Tragos intentionally hurts a young wrestler ... Tragos puts a referee in the hospital ... The double wristlock ... Ray Steele ... Cauliflower ears ... Lou's ignores his father's advice

3

Wrestling in Iowa ... Life on the road ... Traveling with Sol Slagel ... Mother and daughter tag team ... Wrestling in Minnesota for Tony Stecher ... The sad story of Joe Stecher ... Fred Grobmier, the Iowa Cornstalk, hustles the locals ... Lou meets the legendary Farmer Burns ... The story of Frank Gotch ...

4

Lou's introduction to "Strangler" Ed Lewis ... Lou's memories of Ed Lewis ... The stranglehold ... The impact Joe "Toots" Mondt had on wrestling ... The Gold Dust Trio ... Ed Lewis wins the world title ... Stanislaus Zbyszko double crosses world champion Wayne Munn ... Ed Lewis and Joe Stecher settle accounts ... Toots Mondt gets a piece of the New York office ... Jim Londos ... The Ed Lewis-Billy Sandow partnership ... Gus Sonnenberg takes a beating on the Los Angeles streets ... Ed Lewis' famous quote ... The Battle of the Bite ... John Pesek refuses to lose to Lewis ... Toots Mondt lays a trap for Jim Londos ... Peace treaty ... Monopoly ... Jack Pfefer exposes the wrestling business in a mainstream newspaper ... The world title mess ... Ed Lewis' last competitive match

5

Lou returns to St. Louis ... Being humiliated during a match with Ed Lewis ... The lowdown on Toots Mondt ... Barely making ends meet ... Wrestling for Joe Malcewicz ... Working out with Ad Santel ... Learning about hooking ... Wrestling in the main events ... Returning again to St. Louis

6

Events leading up to Lou becoming the world champion ... George and Babe Zaharias ... Lou vs Everette Marshall for the title ... Refusing to sign a contract with Tom Packs and Billy Sandow ... Steve Casey wins the title and takes advantage of Lou ... Lou gets revenge on Casey

7

Packs agrees to return the title to Lou ... Lou again wins the title from Marshall ... The percentage paid the champion ... Meeting and dropping the title to Bronko Nagurski ... Recuperating from a fractured kneecap ... Buying a Doberman Pinscher ... Traveling with Ray Steele ... Working for "Dogs for Defense" ... Troubled marriage ... From the frying pan into the fire ... A-1 status ... Drafted into the Army

8

Shipped to Fort Lewis, Washington ... A meeting with a general ... Dr. John Bonica ... Tom Packs' financial problems ... Buying the St. Louis promotion ... Memories of Buddy Rogers ... A warning to Rogers ... Rogers insults Ed Lewis ... Gorgeous George and his predecessors ... Kissed by Gypsy Rose Lee ... Gorgeous George on "The Bob Hope Show" ... The birth and growth of wrestling on television

9

Sam Muchnick and the National Wrestling Alliance ... Cooperating with Muchnick ... The National Wrestling Association ... The story behind the planned Orville Brown-Lou Thesz title match ... Lou is recognized as the "official" NWA world heavyweight champion ... Contract stipulations ... Wrestlers who tried to shoot on Lou ... Shooting match with Paul Boesch ...

10

Blood and "blood capsules" ... Danny McShain and the blade ... The story of Antonino Rocca ... Rocca skips out on his bookings ... Morris Sigel tried to get Rocca banned ... A plea from Rocca and Kola Kwariani ... Louie Miller threatens Rocca and Kwariani with a gun ... The downfall of Rocca at the hands of the New York promoters ... Memories of Verne Gagne, Bill Miller, "Iron" Mike DiBiase, and Ruffy Silverstein

11

Southern California ... Publicity shots with famous entertainers ... Scuffle in the Melody Room nightclub ... California promoters, Cal Eaton, Hugh Nichols, Johnny Doyle and Mike Hirsch ... Women troubles for Cal Eaton ... Stalked by a Hollywood starlet ... Baron Michele Leone ... A record gate of $103,277 ... Unifying the world titles

12

Problems with the NWA ... Women and midgets ... NWA conventions ... Friendship with Eddie Einhorn ... Building the Montreal territory ... Black trunks and boots ... wrestling vs. working ... Wrestling in tank towns and substandard rings ... Ed Lewis works as Lou's advance publicity man ... Australian tour

13

Tour of the Far East ... Fighting for his money in Australia ... Booked in Singapore against Emile "King Kong" Czaja ... Wrestling in Japan against Rikidozan ...

14

Negotiating with Sam Muchnick ... Dropping the title to Dick Hutton ... Headed to Europe ... Wrestling Dara Singh in London ... Bert Assirati ... Impressed by Felix Miquet

15

Sam Muchnick's appeal to Lou ... Thesz win the world title from Buddy Rogers ... Helping build Edouard Carpentier's reputation ... Verne Gagne and the creation of the American Wrestling Association ... Buddy Rogers, the first WWWF heavyweight champion ... The story of why Bruno Sammartino never wrestled Lou for the title ... Lou agrees to drop the title to Gene Kiniski ... Free-lancing again ... Lou's last visit with Ed Lewis

16

Return to India ... Wrestling Tiger Joginder Singh ... Working for Nashville promoter Nick Gulas ... Promotional war ... Working for the opposition ... Meeting Charlie ...

17

Semi-retirement ... Wrestling on benefit shows ... Paul Bowser gets drunk ... Heated discussion with Primo Carnera and his manager ... Jack Sharkey vs. Primo Carnera ... Lou destroys Carnera in a match with Jack Dempsey as referee ... George Mitchell, aka Chief Chewacki ... Andre the Giant drinks a case of wine, before he wrestles ... Johnny Valentine rides a Brahma bull ... Valentine boxes with Joe Pazandak .... Tim Woods loses a finger ... Joe Scarpello embarrasses Ruffy Silverstein ... Lou makes Silverstein pay for not listening ... Verne Gagne teaches Dick the Bruiser a lesson ...

18

Wrestling in the modern era ... Vince McMahon Jr. ... "Hulkamania" ... The rise of the WWF ... Blame to the NWA ... Lou's final match at 74 years old ... Union of Wrestling Forces International (UWFI) ... Mike Mazurki and the Cauliflower Alley Club ...

Addendum: Thesz Sez ...

Roy Dunn ... Ray Eckert's career comes to an end ... George "Superman" Reeves tried to get into wrestling ... Mississippi Valley Sports Club Office ... Free tire replacement ... A duck dinner in Seattle ... Performing as "Big Julie" in "Guys and Dolls" ... Life on the road with Ed Lewis ... Fred Atkins and Lou rib Ed Lewis ... Ed Lewis and sex ... Jack Pfefer and Toots Mondt ... Jack Pfefer and Lou Kesz ... Lou kills Dory Funk Sr.'s territory ... Fred Kohler gets behind Ed Lewis ... Ed Lewis and Jack Sherry ... Card games and hustles ... Jim Londos tries to steal the St. Louis promotion ... Londos claims he could beat Ed Lewis ... Tom Packs sells his business to Lou ... Mixed matches with boxers ... Ray Steele pins Kingfish Levinsky ... Lou wrestles Jersey Joe Walcott ... Lou tries to train Joe Louis and Big Daddy Lipscomb ... Problems with Sandor Szabo ... Freddie Blassie scaring Japanese children ... Stanislaus Zbyszko and Ed Lewis ... Ted "King Kong" Cox runs over a deer ... Kind words for the legendary Dusek brothers ... The wrestling bear acts ... Toru Tanaka chooses the bear over Lou ... Lou's outside investments ... Two promotional opportunities that failed ... Max Baer as a wrestling referee ... Martin "The Blimp" Levy ... A rib on Larry Moquin ... Moquin gets his revenge ... Tim Woods ribs Lou about his age ... John Pesek plays Lou against Sam Muchnick ... Lou's .22 rifle and the mark ... Vic Christy plants a smoke bomb ... Vic Christy pulls a fast one on Lord Blears ... Vic and the referee pull a rib on Lou and beat him in the ring ... Ed Lewis and good food ... The oldtimers and tough wrestlers ... Carnival wrestlers and AT shows ... Ray Gunkel backs down Buddy Fuller ... Bulldog Jackson pins himself

Photo Gallery

Index

|

|

Lou Thesz is widely considered to be one of the greatest wrestling performers, and many also consider him to be one of the best hookers of his time, even though he didn't have a typical amateur background in wrestling. He started his training to be a professional in 1932 at the age of 16 after being spotted as a stand-out Greco-Roman amateur wrestler by John Zastrow. He would go on to wrestle in every decade until his final match at the age of 74 in 1990, along the way holding the NWA world heavyweight championship three times, for a combined total of ten years, three months and nine days.

"HOOKER," written by Lou Thesz with Kit Bauman, is a surprisingly, bluntly honest book. Lou Thesz hides none of his opinions and speaking openly about his peers and his own career inside the squared circle. Although he admits he doesn't remember everything precisely, and stresses the memories and matches he recalls are ones that held an impact in his life, or stood out for an unusual reason, where as most occasions were the same ole-same ole arrive at a town, wrestle, and drive to the next town. Delving deep into everything, from his training with George Tragos and Ed "Strangler" Lewis, to road stories and matches along the way with everyone from Everett Marshall, in 1937, to "Nature Boy" Buddy Rogers, in 1963. He speaks of his admiration for the history of wrestling and his shyness when he met with the legendary Martin "Farmer" Burns, but also talks just as passionately of his dislike for people such as "Toots" Mondt. Up until 1966, when he lost his last NWA world heavyweight title to Gene Kiniski, he talks in detail about the key moments of his career, all the while backed up by Kit Bauman's excellent and informative endnotes, researched with J. Michael Kenyon. Lou Thesz barely touches on the '70s, '80s and '90s, speaking of his refereeing and his brief association with shoot style wrestling in Japan. Insead, he chooses to reminisce fondly about his beloved catch-as-catch-can style.

All in all, the 2011 revised edition of Lou Thesz's "HOOKER" is one man's philosophy and outlook on the world of wrestling, biased and very opinionated in his views, yet smoothed over by Kit Bauman's contribution. At first, I dreaded the thought of informational endnotes at the conclusion of every chapter. However, I found them very helpful and useful whilst reading the book. Not only do they correct the errors of Lou's memory at times, but they provide additional information and stories that simply would not have fitted well into the actual chapter. With a section after the biography itself dedicated to Lou's stories and memories of various topics, and 215 black-and-white photos, the book is truly a must-read for anyone who wants an inside look at what it took to be a professional wrestler in the "golden era of wrestling."

Jimmy Wheeler, West Midlands, UK

|